Post by zarahan on Sept 1, 2018 23:53:35 GMT -5

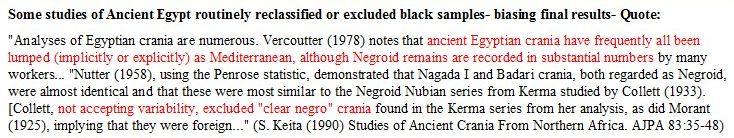

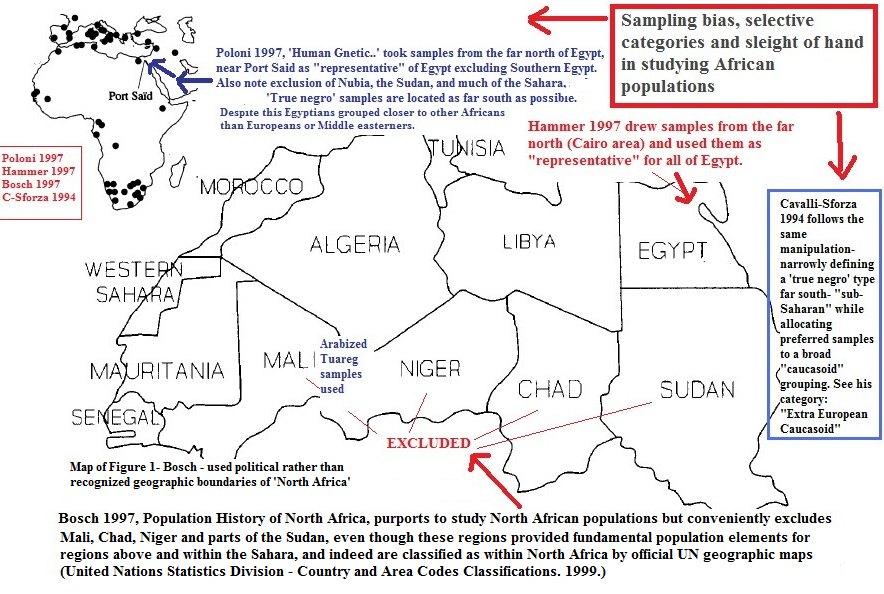

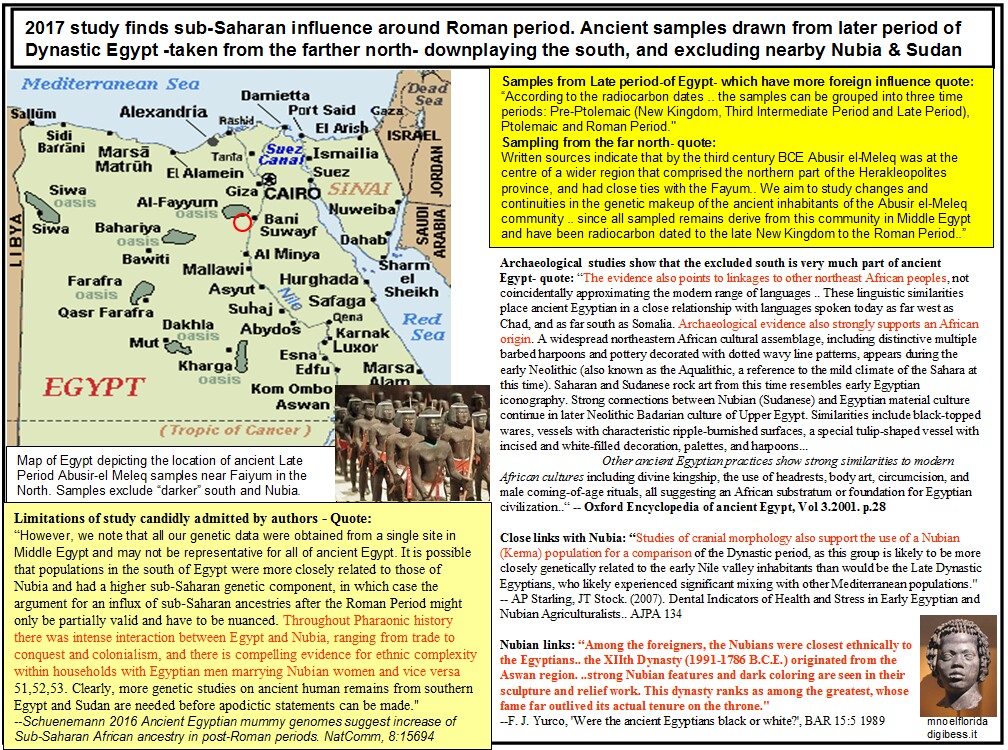

Credible peer-review scientists (Gourdine, Keita, Anselin) critique Abusir-El Meleq ancient DNA study for several flaws: (a) limited (3 samples) and skewed sampling excluding southern Egypt and other Africans like Nubians, (b) skewed on normal, full presentation of data and alternative explanations (such as using only Late Period samples excluding 3,000 years of prior Egyptian history, and (c) stereotypical conceptions of ‘Africans’ as only peoples ‘south’ of the Sahara.

Study implied that ancient Egyptians came from the Asia, and that "sub-Saharan" Africans are recent due to the Islamic slave trades:

QUOTES: “Schuenemann et al.1 seemingly suggest, based largely on the results of an ancient DNA study of later period remains from northern Egypt, that the ‘ancient Egyptians’ (AE) as an entity came from Asia (the Near East, NE), and that modern Egyptians “received additional sub- Saharan African (SSA) admixtures in recent times” after the latest period of the pharaonic era due to the “trans-Saharan slave trade and Islamic expansion..” There are alternative interpretations of the results but which were not presented as is traditionally done, with the exception of the admission that results from southern Egyptians may have been different. The alternative interpretations involve three major considerations: 1) sampling and methodology, 2) historiography and 3) definitions as they relate to populations, origins and evolution.” Tiny sample sizes: “The whole genome sample size is too small (n=3) to accurately permit a discussion of all Egyptian population history from north to south.”

Other DNA data show substantial African affinity: “Results that are likely reliable are from studies that analyzed short tandem repeats (STRs) from Amarna royal mummies5 (1,300 BC), and of Ramesses III (1,200 BC)6; Ramesses III had the Y chromosome haplogroup E1b1a, an old African lineage7. Our analysis of STRs from Amarna and Ramesside royal mummies with popAffiliator18 based on the same published data5,6 indicates a 41.7% to 93.9% probability of SSA affinities (see Table 1); most of the individuals had a greater probability of affiliation with “SSA” which is not the only way to be “African”- a point worth repeating.”

Arbitrary definition of some DNA haplogroups as ‘Asian’ problematic: “Conceptually what genetic markers are considered to be “African” or “Asian” .. For example, the E1b1b1 (M35/78) lineage found in one Abusir el-Meleq sample is found not only in northern Africa, but is also well represented in eastern Africa7 and perhaps was taken to Europe across the Mediterranean before the Holocene (Trombetta, personal communication). E lineages are found in high frequency (>70%) among living Egyptians in Adaima9. The authors define all mitochondrial M1 haplogroups as “Asian” which is problematic. M1 has been postulated to have emerged in Africa10, and there is no convincing evidence supporting an M1 ancestor in Asia: many M1 daughter haplogroups (M1a) are clearly African in origin and history10. The M1a1, M1a2a, M1a1i, M1a1e variants found in the Abusir el-Meleq samples1 predate Islam and are abundant in SSA groups10, particularly in East Africa.”

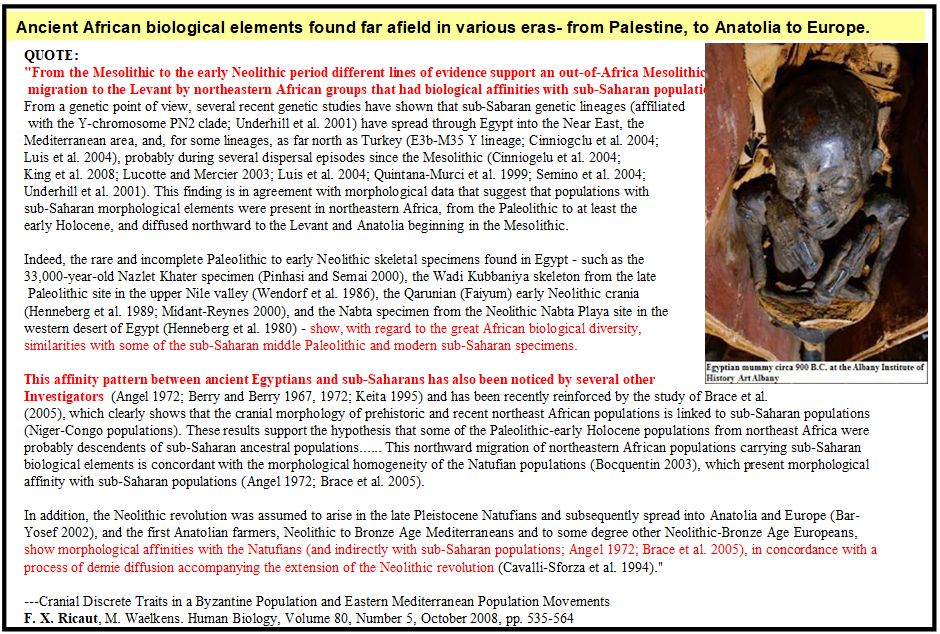

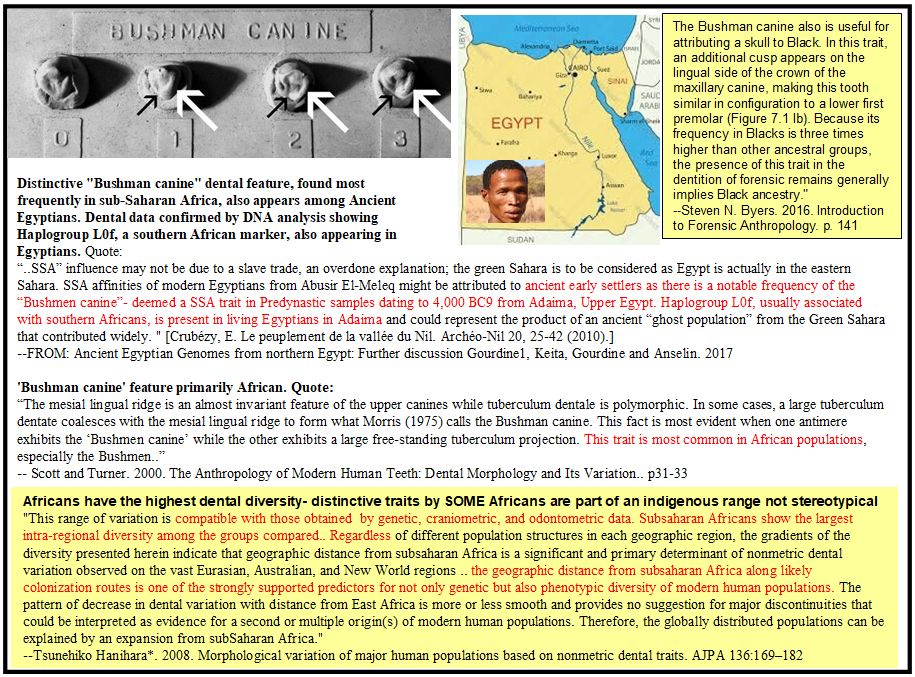

So called “sub-Saharan” patterns in place from the beginning in Egypt and are not merely the product of the ‘slave trade.’ “Furthermore, SSA groups indicated to have contributed to modern Egypt do not match the Muslim trade routes that have been well documented11 as SSA groups from the great lakes and southern African regions were largely absent in the internal trading routes that went north to Egypt. It is important to note that “SSA” influence may not be due to a slave trade, an overdone explanation; the green Sahara is to be considered as Egypt is actually in the eastern Sahara. SSA affinities of modern Egyptians from Abusir El-Meleq might be attributed to ancient early settlers as there is a notable frequency of the “Bushmen canine”- deemed a SSA trait in Predynastic samples dating to 4,000 BC9 from Adaima, Upper Egypt. Haplogroup L0f, usually associated with southern Africans, is present in living Egyptians in Adaima9 and could represent the product of an ancient “ghost population” from the Green Sahara that contributed widely. Distributions and admixtures in the African past may not match current “SSA” groups12.”

Definition of ‘African’ stereotypical, even as strangely, authors exclude many actual African samples near Egypt from the data

“Schuenemann et al.1 seem to implicitly suggest that only SSA equals Africa and that there are no interconnections between the various regions of Africa not rooted in the slave trade, a favorite trope. It has to be noted too that that in the Islamic armies that entered Egypt that there were a notable number of eastern Africans. It is not clear why there is an emphasis on ‘sub-Saharan’ when no Saharan or supra-Saharan population samples--empirical or modelled are considered; furthermore, there is no one way to be “sub-Saharan.” In this study northern tropical Africans, such as lower and upper Nubians and adjacent southern Egyptians and Saharans were not included as comparison groups, as noted by the authors themselves.”

FROM: -Gourdine JP, Keita SOY, Gourdine JL, Anselin A, 2018. Ancient Egyptian Genomes from northern Egypt

^^Peer review critique above points out several flaws in Abusir study.. Note the detailed

historical and anthropological data excluded above...

Test of full peer critique: osf.io/ecwf3/

Study implied that ancient Egyptians came from the Asia, and that "sub-Saharan" Africans are recent due to the Islamic slave trades:

QUOTES: “Schuenemann et al.1 seemingly suggest, based largely on the results of an ancient DNA study of later period remains from northern Egypt, that the ‘ancient Egyptians’ (AE) as an entity came from Asia (the Near East, NE), and that modern Egyptians “received additional sub- Saharan African (SSA) admixtures in recent times” after the latest period of the pharaonic era due to the “trans-Saharan slave trade and Islamic expansion..” There are alternative interpretations of the results but which were not presented as is traditionally done, with the exception of the admission that results from southern Egyptians may have been different. The alternative interpretations involve three major considerations: 1) sampling and methodology, 2) historiography and 3) definitions as they relate to populations, origins and evolution.” Tiny sample sizes: “The whole genome sample size is too small (n=3) to accurately permit a discussion of all Egyptian population history from north to south.”

Other DNA data show substantial African affinity: “Results that are likely reliable are from studies that analyzed short tandem repeats (STRs) from Amarna royal mummies5 (1,300 BC), and of Ramesses III (1,200 BC)6; Ramesses III had the Y chromosome haplogroup E1b1a, an old African lineage7. Our analysis of STRs from Amarna and Ramesside royal mummies with popAffiliator18 based on the same published data5,6 indicates a 41.7% to 93.9% probability of SSA affinities (see Table 1); most of the individuals had a greater probability of affiliation with “SSA” which is not the only way to be “African”- a point worth repeating.”

Arbitrary definition of some DNA haplogroups as ‘Asian’ problematic: “Conceptually what genetic markers are considered to be “African” or “Asian” .. For example, the E1b1b1 (M35/78) lineage found in one Abusir el-Meleq sample is found not only in northern Africa, but is also well represented in eastern Africa7 and perhaps was taken to Europe across the Mediterranean before the Holocene (Trombetta, personal communication). E lineages are found in high frequency (>70%) among living Egyptians in Adaima9. The authors define all mitochondrial M1 haplogroups as “Asian” which is problematic. M1 has been postulated to have emerged in Africa10, and there is no convincing evidence supporting an M1 ancestor in Asia: many M1 daughter haplogroups (M1a) are clearly African in origin and history10. The M1a1, M1a2a, M1a1i, M1a1e variants found in the Abusir el-Meleq samples1 predate Islam and are abundant in SSA groups10, particularly in East Africa.”

So called “sub-Saharan” patterns in place from the beginning in Egypt and are not merely the product of the ‘slave trade.’ “Furthermore, SSA groups indicated to have contributed to modern Egypt do not match the Muslim trade routes that have been well documented11 as SSA groups from the great lakes and southern African regions were largely absent in the internal trading routes that went north to Egypt. It is important to note that “SSA” influence may not be due to a slave trade, an overdone explanation; the green Sahara is to be considered as Egypt is actually in the eastern Sahara. SSA affinities of modern Egyptians from Abusir El-Meleq might be attributed to ancient early settlers as there is a notable frequency of the “Bushmen canine”- deemed a SSA trait in Predynastic samples dating to 4,000 BC9 from Adaima, Upper Egypt. Haplogroup L0f, usually associated with southern Africans, is present in living Egyptians in Adaima9 and could represent the product of an ancient “ghost population” from the Green Sahara that contributed widely. Distributions and admixtures in the African past may not match current “SSA” groups12.”

Definition of ‘African’ stereotypical, even as strangely, authors exclude many actual African samples near Egypt from the data

“Schuenemann et al.1 seem to implicitly suggest that only SSA equals Africa and that there are no interconnections between the various regions of Africa not rooted in the slave trade, a favorite trope. It has to be noted too that that in the Islamic armies that entered Egypt that there were a notable number of eastern Africans. It is not clear why there is an emphasis on ‘sub-Saharan’ when no Saharan or supra-Saharan population samples--empirical or modelled are considered; furthermore, there is no one way to be “sub-Saharan.” In this study northern tropical Africans, such as lower and upper Nubians and adjacent southern Egyptians and Saharans were not included as comparison groups, as noted by the authors themselves.”

FROM: -Gourdine JP, Keita SOY, Gourdine JL, Anselin A, 2018. Ancient Egyptian Genomes from northern Egypt

^^Peer review critique above points out several flaws in Abusir study.. Note the detailed

historical and anthropological data excluded above...

Test of full peer critique: osf.io/ecwf3/

.

.