Post by anansi on Jan 30, 2012 2:25:07 GMT -5

This need to be a Hollywood movie,I first came across his name in a little booklet I while browsing through revolution bookstore in Harlem yrs ago and that sparked my interest the story of Bessi Coleman may have came to me from Gil Noble Like It Is,recently Nesben Of ESR had re-spark that interest with his post on the up coming movie Red Tails about African American WWII fighter pilots here are couple of articles that I am posting about them,in The movie Tuskeegee airmen If you remember a character who flew in France during WWI that was later to be an instructor to the WWII pilots I include his story also.

He challenged Hermann Goring to a duel over the English Channel in World War II.

In 1930, when future Ethiopian ruler Haile Selassie was planning a lavish ceremony to celebrate his coronation as emperor, he sent an emissary to a 33-year-old U.S.-based aviator, Hubert Fauntleroy Julian. Aviation had come to Ethiopia only the year before, with the arrival of a French Potez 25 biplane piloted by André Maillet, but the modernity-obsessed Selassie hoped to put on an aerial display, with a flamboyant performer who would attract the world’s attention. Julian, known in New York as the “Black Eagle of Harlem” and sometimes called the “Negro Lindbergh,” was the perfect choice.

At the emperor-elect’s request, the Ethiopian Imperial Air Force, which consisted of two Junkers monoplanes, a Gipsy Moth, and two French pilots, performed a pre-coronation show. In an unplanned flourish, Julian leapt from Maillet’s airplane, parachuting to the feet of Selassie, who was so pleased that he bestowed Ethiopian citizenship on Julian, the rank of colonel, and awarded him the Order of Menelik, the empire’s highest honor.

Julian’s glory was short-lived. Four months later, during a coronation dress rehearsal in Addis Ababa, Julian lost control of the de Havilland Gipsy Moth he was flying. As the emperor-elect looked on in fury, Julian made a crash landing into a eucalyptus tree. The Moth had been Selassie’s personal airplane, a gift from Selfridge’s department store in London, and Julian was expelled from the country amid allegations that he had stolen the aircraft. He accused the Ethiopian air force’s French airmen of sabotaging him, but conceded in his 1964 memoir, Black Eagle, that “a crash at an air display watched by foreigners whom the Emperor wanted to impress was clearly a disaster.”

So the Black Eagle returned to Harlem. For the rest of his life Julian would continue to promote himself as Selassie’s air marshal, but Ethiopia would prove to be only a brief chapter in the Black Eagle’s just-true-enough life story.

It was in Ethiopia, in 2001, that I first heard of Julian. I was visiting a family of Jamaican Rastafarians who had immigrated to Ethiopia, and while we were discussing the history of other West Indians who had settled in the country, Julian’s name came up.

The Black Eagle is remembered in Ethiopia for his famous pre-coronation crash, and for his vocal anti-fascist stance in the days preceding World War II. He was spoken of reverently—although some of the details of his life were a bit muddled—and is remembered as someone who tried to do heroic things. Even though he didn’t always succeed, he’s considered a hero for trying.

In Julian’s autobiography, I learned that he himself muddled some of the details of his life. He was born in 1897 in the British colony of Trinidad, the son of a cocoa plantation manager. He writes that he grew up in a middle class neighborhood in the capital, Port of Spain, where he attended a British-administered boys’ school. The island’s first exposure to flight ended badly: In January 1913, aircraft designer Frank Boland crashed a tail-less biplane over the Queen’s Park Savannah, near Julian’s home, and was killed instantly. Julian, feeling the need to make the crash part of his personal narrative, moved it back to 1909 in his autobiography, placing himself at the scene.

I would learn that this compulsion to embellish was an essential part of Julian’s character. While these embellishments made it tempting to dismiss Julian as a charlatan, each time I dug deeper I found that his stories usually contained ample elements of truth.

www.airspacemag.com/history-of-flight/The-Black-Eagle-of-Harlem.html

Bessie Coleman, the first African American female pilot, grew up in a cruel world of poverty and discrimination. The year after her birth in Atlanta, Texas, an African American man was tortured and then burned to death in nearby Paris for allegedly raping a five-year-old girl. The incident was not unusual; lynchings were endemic throughout the South. African Americans were essentially barred from voting by literacy tests. They couldn't ride in railway cars with white people, or use a wide range of public facilities set aside for whites. When young Bessie first went to school at the age of six, it was to a one-room wooden shack, a four-mile walk from her home. Often there wasn't paper to write on or pencils to write with.

When Coleman turned 23 she headed to Chicago to live with two of her older brothers, hoping to make something of herself. But the Windy City offered little more to an African American woman than did Texas. When Coleman decided she wanted to learn to fly, the double stigma of her race and gender meant that she would have to travel to France to realize her dreams.

It was soldiers returning from World War I with wild tales of flying exploits who first interested Coleman in aviation. She was also spurred on by her brother, who taunted her with claims that French women were superior to African American women because they could fly. In fact, very few American women of any race had pilot's licenses in 1918. Those who did were predominantly white and wealthy. Every flying school that Coleman approached refused to admit her because she was both black and a woman. On the advice of Robert Abbott, the owner of the "Chicago Defender" and one of the first African American millionaires, Coleman decided to learn to fly in France.

Coleman learned French at a Berlitz school in the Chicago loop, withdrew the savings she had accumulated from her work as a manicurist and the manager of a chili parlor, and with the additional financial support of Abbott and another African American entrepreneur, she set off for Paris from New York on November 20, 1920. It took Coleman seven months to learn how to fly. The only non-Caucasian student in her class, she was taught in a 27-foot biplane that was known to fail frequently, sometimes in the air. During her training Coleman witnessed a fellow student die in a plane crash, which she described as a "terrible shock" to her nerves. But the accident didn't deter her: In June 1921, the Fédération Aéronautique Internationale awarded her an international pilot's license.

When Coleman returned to the U.S. in September 1921, scores of reporters turned out to meet her. The "Air Service News" noted that Coleman had become "a full-fledged aviatrix, the first of her race." She was invited as a guest of honor to attend the all-black musical "Shuffle Along." The entire audience, including the several hundred whites in the orchestra seats, rose to give the first African American female pilot a standing ovation.

Over the next five years Coleman performed at countless air shows. The first took place on September 3, 1922, in Garden City, Long Island. The "Chicago Defender" publicized the event saying the "wonderful little woman" Bessie Coleman would do "heart thrilling stunts." According to a reporter from Kansas, as many as 3,000 people, including local dignitaries, attended the event. Over the following years, Coleman used her position of prominence to encourage other African Americans to fly. She also made a point of refusing to perform at locations that wouldn't admit members of her race.

Coleman took her tragic last flight on April 30, 1926, in Jacksonville, Florida. Together with a young Texan mechanic called William Wills, Coleman was preparing for an air show that was to have taken place the following day. At 3,500 feet with Wills at the controls, an unsecured wrench somehow got caught in the control gears and the plane unexpectedly plummeted toward earth. Coleman, who wasn't wearing a seat-belt, fell to her death.

About 10,000 mourners paid their last respects to the first African American woman aviator, filing past her coffin in Chicago South's Side. Her funeral was attended by several prominent African Americans and it was presided over by Ida B. Wells, an outspoken advocate of equal rights. But despite the massive turnout and the tributes paid to Coleman during the service, several black reporters believed that the scope of Coleman's accomplishments had never truly been recognized during her lifetime. An editorial in the "Dallas Express" stated, "There is reason to believe that the general public did not completely sense the size of her contribution to the achievements of the race as such."

Coleman has not been forgotten in the decades since her death. For a number of years starting in 1931, black pilots from Chicago instituted an annual fly over of her grave. In 1977 a group of African American women pilots established the Bessie Coleman Aviators Club. And in 1992 a Chicago City council resolution requested that the U.S. Postal Service issue a Bessie Coleman stamp. The resolution noted that "Bessie Coleman continues to inspire untold thousands even millions of young persons with her sense of adventure, her positive attitude, and her determination to succeed."

www.pbs.org/wgbh/amex/flygirls/peopleevents/pandeAMEX02.html

October 12, 2010, marks the forty-ninth anniversary of the death of Eugene Jacques Bullard at the age of 67. Bullard is considered to be the first African-American military pilot to fly in combat, and the only African-American pilot in World War I. Ironically, he never flew for the United States.

Born October 9, 1895, in Columbus, Georgia, to William Bullard, a former slave, and Josephine Bullard, Eugene’s early youth was unhappy. He made several unsuccessful attempts to run away from home, one of which resulted in his being returned home and beaten by his father.

In 1906, at the age of 11, Bullard ran away for good, and for the next six years, he wandered the South in search of freedom. In 1912 he stowed away on the Marta Russ, a German freighter bound for Hamburg, and ended up in Aberdeen, Scotland. From there he made his way to London, where he worked as a boxer and slapstick performer in Belle Davis’s Freedman Pickaninnies, an African American entertainment troupe. In 1913, Bullard went to France for a boxing match. Settling in Paris, he became so comfortable with French customs that he decided to make a home there. He later wrote, “… it seemed to me that French democracy influenced the minds of both black and white Americans there and helped us all act like brothers.”

After World War I had begun in the summer of 1914, Bullard enlisted in the French Foreign Legion. While serving with the 170th Infantry Regiment, Bullard fought in the the Battle of Verdun (February to December 1916), where he was wounded seriously. He was taken from the battlefield and sent to Lyon to recuperate. While on leave in Paris, Bullard bet a friend $2,000 that despite his color he could enlist in the French flying service. Bullard’s determination paid off, and in November 1916 he entered the Aéronautique Militaire.

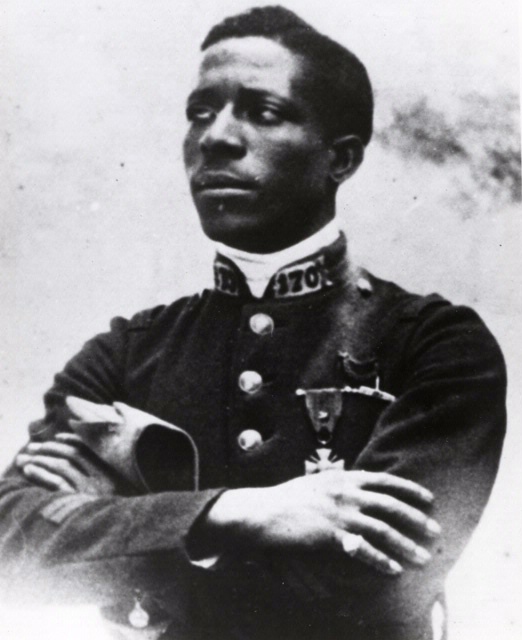

Eugene Bullard

Bullard began flight training at Tours in 1916 and received his wings in May 1917. He was first assigned to Escadrille Spa 93, and then to Escadrille Spa 85 in September 1917, where he remained until he left the Aéronautique Militaire. In November 1917, Bullard claimed two aerial victories, a Fokker Triplane and a Pfalz D.III, but neither could be confirmed. (Some accounts say that one victory was confirmed.) During his flying days, Bullard is said to have had an insignia on his Spad 7 C.1 that portrayed a heart with a dagger running through it and the slogan “All Blood Runs Red.” Reportedly, Bullard flew with a mascot, a Rhesus Monkey named “Jimmy.”

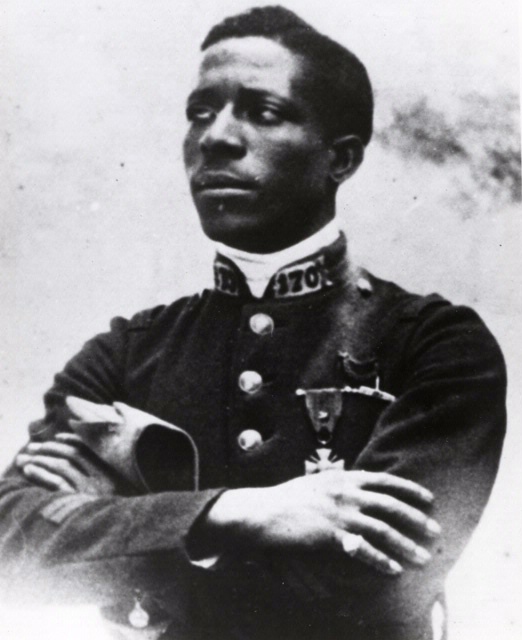

Eugene Bullard with his Rhesus monkey, Jimmy

After the United States entered the war in 1917, Bullard attempted to join the U.S. Air Service, but he was not accepted, ostensibly because he was an enlisted man, and the Air Service required pilots to be officers and hold at least the rank of First Lieutenant. In actuality, he was rejected because of the racial prejudice that existed in the American military during that time. Bullard returned to the Aéronautique Militaire, but he was summarily removed after an apparent confrontation with a French officer. He returned to the 170th Infantry Regiment until his discharge in October 1919.

After the war Bullard remained in France, where he worked in a nightclub called Zelli’s in the Montmartre district of Paris, owned a nightclub (Le Grand Duc) and an American-style bar (L’Escadrille), operated an athletic club, and married a French woman, Marcelle de Straumann. During this time Bullard rubbed elbows with notables like Langston Hughes, F. Scott Fitzgerald, and Josephine Baker.

By the late 1930s, however, the clouds of war began to change Bullard’s life dramatically. Even before World War II officially began in 1939, Bullard became involved in espionage activities against French fifth columnists who supported the Nazis. When war came he enlisted as a machine gunner in the 51st Infantry Regiment, and was severely wounded by an exploding artillery shell. Fearing capture by the Nazis, he made his way to Spain, Portugal, and eventually the United States, settling in the Harlem district of New York City.

After his arrival in New York, Bullard worked as a security guard and longshoreman. In the post-World War II years, Bullard took up the cause of civil rights. In the summer of 1949, he was involved in an altercation with the police and a racist mob at a Paul Robeson concert in Peekskill, New York, in which he was beaten by police. Another incident involved a bus driver who ordered Bullard to sit the back of his bus. These events left Bullard deeply disillusioned with the United States, and he returned to France, but was unable to resume his former life there.

During his lifetime, the French showered Bullard with honors, and in 1954, he was one of three men chosen to relight the everlasting flame at the Tomb of the Unknown Soldier in Paris. In October 1959 he was made a knight of the Legion of Honor, the highest ranking order and decoration bestowed by France. It was the fifteenth decoration given to him by the French government.

In the epilogue to his well-researched book, Eugene Bullard, Black Expatriate in Jazz-Age Paris (Athens: Univ. of Georgia Press, 2000), Craig Lloyd points out the poignancy of Bullard’s situation in the United States: “The contrast between Eugene Bullard’s unrewarding years of toil and trouble early and late in life in the United States and his quarter-century of much-heralded achievement in France illustrates dramatically … the crippling disabilities imposed on the descendants of Americans of African ancestry … .”

In 1992, the McDonnell Douglas Corporation donated to the National Air and Space Museum a bronze portrait head of Bullard, created by Eddie Dixon, an African American sculptor. This work is displayed in the museum’s Legend, Memory and the Great War in the Air gallery.

He challenged Hermann Goring to a duel over the English Channel in World War II.

In 1930, when future Ethiopian ruler Haile Selassie was planning a lavish ceremony to celebrate his coronation as emperor, he sent an emissary to a 33-year-old U.S.-based aviator, Hubert Fauntleroy Julian. Aviation had come to Ethiopia only the year before, with the arrival of a French Potez 25 biplane piloted by André Maillet, but the modernity-obsessed Selassie hoped to put on an aerial display, with a flamboyant performer who would attract the world’s attention. Julian, known in New York as the “Black Eagle of Harlem” and sometimes called the “Negro Lindbergh,” was the perfect choice.

At the emperor-elect’s request, the Ethiopian Imperial Air Force, which consisted of two Junkers monoplanes, a Gipsy Moth, and two French pilots, performed a pre-coronation show. In an unplanned flourish, Julian leapt from Maillet’s airplane, parachuting to the feet of Selassie, who was so pleased that he bestowed Ethiopian citizenship on Julian, the rank of colonel, and awarded him the Order of Menelik, the empire’s highest honor.

Julian’s glory was short-lived. Four months later, during a coronation dress rehearsal in Addis Ababa, Julian lost control of the de Havilland Gipsy Moth he was flying. As the emperor-elect looked on in fury, Julian made a crash landing into a eucalyptus tree. The Moth had been Selassie’s personal airplane, a gift from Selfridge’s department store in London, and Julian was expelled from the country amid allegations that he had stolen the aircraft. He accused the Ethiopian air force’s French airmen of sabotaging him, but conceded in his 1964 memoir, Black Eagle, that “a crash at an air display watched by foreigners whom the Emperor wanted to impress was clearly a disaster.”

So the Black Eagle returned to Harlem. For the rest of his life Julian would continue to promote himself as Selassie’s air marshal, but Ethiopia would prove to be only a brief chapter in the Black Eagle’s just-true-enough life story.

It was in Ethiopia, in 2001, that I first heard of Julian. I was visiting a family of Jamaican Rastafarians who had immigrated to Ethiopia, and while we were discussing the history of other West Indians who had settled in the country, Julian’s name came up.

The Black Eagle is remembered in Ethiopia for his famous pre-coronation crash, and for his vocal anti-fascist stance in the days preceding World War II. He was spoken of reverently—although some of the details of his life were a bit muddled—and is remembered as someone who tried to do heroic things. Even though he didn’t always succeed, he’s considered a hero for trying.

In Julian’s autobiography, I learned that he himself muddled some of the details of his life. He was born in 1897 in the British colony of Trinidad, the son of a cocoa plantation manager. He writes that he grew up in a middle class neighborhood in the capital, Port of Spain, where he attended a British-administered boys’ school. The island’s first exposure to flight ended badly: In January 1913, aircraft designer Frank Boland crashed a tail-less biplane over the Queen’s Park Savannah, near Julian’s home, and was killed instantly. Julian, feeling the need to make the crash part of his personal narrative, moved it back to 1909 in his autobiography, placing himself at the scene.

I would learn that this compulsion to embellish was an essential part of Julian’s character. While these embellishments made it tempting to dismiss Julian as a charlatan, each time I dug deeper I found that his stories usually contained ample elements of truth.

www.airspacemag.com/history-of-flight/The-Black-Eagle-of-Harlem.html

Bessie Coleman, the first African American female pilot, grew up in a cruel world of poverty and discrimination. The year after her birth in Atlanta, Texas, an African American man was tortured and then burned to death in nearby Paris for allegedly raping a five-year-old girl. The incident was not unusual; lynchings were endemic throughout the South. African Americans were essentially barred from voting by literacy tests. They couldn't ride in railway cars with white people, or use a wide range of public facilities set aside for whites. When young Bessie first went to school at the age of six, it was to a one-room wooden shack, a four-mile walk from her home. Often there wasn't paper to write on or pencils to write with.

When Coleman turned 23 she headed to Chicago to live with two of her older brothers, hoping to make something of herself. But the Windy City offered little more to an African American woman than did Texas. When Coleman decided she wanted to learn to fly, the double stigma of her race and gender meant that she would have to travel to France to realize her dreams.

It was soldiers returning from World War I with wild tales of flying exploits who first interested Coleman in aviation. She was also spurred on by her brother, who taunted her with claims that French women were superior to African American women because they could fly. In fact, very few American women of any race had pilot's licenses in 1918. Those who did were predominantly white and wealthy. Every flying school that Coleman approached refused to admit her because she was both black and a woman. On the advice of Robert Abbott, the owner of the "Chicago Defender" and one of the first African American millionaires, Coleman decided to learn to fly in France.

Coleman learned French at a Berlitz school in the Chicago loop, withdrew the savings she had accumulated from her work as a manicurist and the manager of a chili parlor, and with the additional financial support of Abbott and another African American entrepreneur, she set off for Paris from New York on November 20, 1920. It took Coleman seven months to learn how to fly. The only non-Caucasian student in her class, she was taught in a 27-foot biplane that was known to fail frequently, sometimes in the air. During her training Coleman witnessed a fellow student die in a plane crash, which she described as a "terrible shock" to her nerves. But the accident didn't deter her: In June 1921, the Fédération Aéronautique Internationale awarded her an international pilot's license.

When Coleman returned to the U.S. in September 1921, scores of reporters turned out to meet her. The "Air Service News" noted that Coleman had become "a full-fledged aviatrix, the first of her race." She was invited as a guest of honor to attend the all-black musical "Shuffle Along." The entire audience, including the several hundred whites in the orchestra seats, rose to give the first African American female pilot a standing ovation.

Over the next five years Coleman performed at countless air shows. The first took place on September 3, 1922, in Garden City, Long Island. The "Chicago Defender" publicized the event saying the "wonderful little woman" Bessie Coleman would do "heart thrilling stunts." According to a reporter from Kansas, as many as 3,000 people, including local dignitaries, attended the event. Over the following years, Coleman used her position of prominence to encourage other African Americans to fly. She also made a point of refusing to perform at locations that wouldn't admit members of her race.

Coleman took her tragic last flight on April 30, 1926, in Jacksonville, Florida. Together with a young Texan mechanic called William Wills, Coleman was preparing for an air show that was to have taken place the following day. At 3,500 feet with Wills at the controls, an unsecured wrench somehow got caught in the control gears and the plane unexpectedly plummeted toward earth. Coleman, who wasn't wearing a seat-belt, fell to her death.

About 10,000 mourners paid their last respects to the first African American woman aviator, filing past her coffin in Chicago South's Side. Her funeral was attended by several prominent African Americans and it was presided over by Ida B. Wells, an outspoken advocate of equal rights. But despite the massive turnout and the tributes paid to Coleman during the service, several black reporters believed that the scope of Coleman's accomplishments had never truly been recognized during her lifetime. An editorial in the "Dallas Express" stated, "There is reason to believe that the general public did not completely sense the size of her contribution to the achievements of the race as such."

Coleman has not been forgotten in the decades since her death. For a number of years starting in 1931, black pilots from Chicago instituted an annual fly over of her grave. In 1977 a group of African American women pilots established the Bessie Coleman Aviators Club. And in 1992 a Chicago City council resolution requested that the U.S. Postal Service issue a Bessie Coleman stamp. The resolution noted that "Bessie Coleman continues to inspire untold thousands even millions of young persons with her sense of adventure, her positive attitude, and her determination to succeed."

www.pbs.org/wgbh/amex/flygirls/peopleevents/pandeAMEX02.html

October 12, 2010, marks the forty-ninth anniversary of the death of Eugene Jacques Bullard at the age of 67. Bullard is considered to be the first African-American military pilot to fly in combat, and the only African-American pilot in World War I. Ironically, he never flew for the United States.

Born October 9, 1895, in Columbus, Georgia, to William Bullard, a former slave, and Josephine Bullard, Eugene’s early youth was unhappy. He made several unsuccessful attempts to run away from home, one of which resulted in his being returned home and beaten by his father.

In 1906, at the age of 11, Bullard ran away for good, and for the next six years, he wandered the South in search of freedom. In 1912 he stowed away on the Marta Russ, a German freighter bound for Hamburg, and ended up in Aberdeen, Scotland. From there he made his way to London, where he worked as a boxer and slapstick performer in Belle Davis’s Freedman Pickaninnies, an African American entertainment troupe. In 1913, Bullard went to France for a boxing match. Settling in Paris, he became so comfortable with French customs that he decided to make a home there. He later wrote, “… it seemed to me that French democracy influenced the minds of both black and white Americans there and helped us all act like brothers.”

After World War I had begun in the summer of 1914, Bullard enlisted in the French Foreign Legion. While serving with the 170th Infantry Regiment, Bullard fought in the the Battle of Verdun (February to December 1916), where he was wounded seriously. He was taken from the battlefield and sent to Lyon to recuperate. While on leave in Paris, Bullard bet a friend $2,000 that despite his color he could enlist in the French flying service. Bullard’s determination paid off, and in November 1916 he entered the Aéronautique Militaire.

Eugene Bullard

Bullard began flight training at Tours in 1916 and received his wings in May 1917. He was first assigned to Escadrille Spa 93, and then to Escadrille Spa 85 in September 1917, where he remained until he left the Aéronautique Militaire. In November 1917, Bullard claimed two aerial victories, a Fokker Triplane and a Pfalz D.III, but neither could be confirmed. (Some accounts say that one victory was confirmed.) During his flying days, Bullard is said to have had an insignia on his Spad 7 C.1 that portrayed a heart with a dagger running through it and the slogan “All Blood Runs Red.” Reportedly, Bullard flew with a mascot, a Rhesus Monkey named “Jimmy.”

Eugene Bullard with his Rhesus monkey, Jimmy

After the United States entered the war in 1917, Bullard attempted to join the U.S. Air Service, but he was not accepted, ostensibly because he was an enlisted man, and the Air Service required pilots to be officers and hold at least the rank of First Lieutenant. In actuality, he was rejected because of the racial prejudice that existed in the American military during that time. Bullard returned to the Aéronautique Militaire, but he was summarily removed after an apparent confrontation with a French officer. He returned to the 170th Infantry Regiment until his discharge in October 1919.

After the war Bullard remained in France, where he worked in a nightclub called Zelli’s in the Montmartre district of Paris, owned a nightclub (Le Grand Duc) and an American-style bar (L’Escadrille), operated an athletic club, and married a French woman, Marcelle de Straumann. During this time Bullard rubbed elbows with notables like Langston Hughes, F. Scott Fitzgerald, and Josephine Baker.

By the late 1930s, however, the clouds of war began to change Bullard’s life dramatically. Even before World War II officially began in 1939, Bullard became involved in espionage activities against French fifth columnists who supported the Nazis. When war came he enlisted as a machine gunner in the 51st Infantry Regiment, and was severely wounded by an exploding artillery shell. Fearing capture by the Nazis, he made his way to Spain, Portugal, and eventually the United States, settling in the Harlem district of New York City.

After his arrival in New York, Bullard worked as a security guard and longshoreman. In the post-World War II years, Bullard took up the cause of civil rights. In the summer of 1949, he was involved in an altercation with the police and a racist mob at a Paul Robeson concert in Peekskill, New York, in which he was beaten by police. Another incident involved a bus driver who ordered Bullard to sit the back of his bus. These events left Bullard deeply disillusioned with the United States, and he returned to France, but was unable to resume his former life there.

During his lifetime, the French showered Bullard with honors, and in 1954, he was one of three men chosen to relight the everlasting flame at the Tomb of the Unknown Soldier in Paris. In October 1959 he was made a knight of the Legion of Honor, the highest ranking order and decoration bestowed by France. It was the fifteenth decoration given to him by the French government.

In the epilogue to his well-researched book, Eugene Bullard, Black Expatriate in Jazz-Age Paris (Athens: Univ. of Georgia Press, 2000), Craig Lloyd points out the poignancy of Bullard’s situation in the United States: “The contrast between Eugene Bullard’s unrewarding years of toil and trouble early and late in life in the United States and his quarter-century of much-heralded achievement in France illustrates dramatically … the crippling disabilities imposed on the descendants of Americans of African ancestry … .”

In 1992, the McDonnell Douglas Corporation donated to the National Air and Space Museum a bronze portrait head of Bullard, created by Eddie Dixon, an African American sculptor. This work is displayed in the museum’s Legend, Memory and the Great War in the Air gallery.