Post by homeylu on Apr 12, 2010 14:41:57 GMT -5

What we know about the Garamante Kingdom is given to us by Greek and Roman sources. According to their oral tradition, the Tuareg are the direct descendants of the Garamantes. Who were these people, and what made them so significant?

The name first assigned to this group of Africans that once thrived in the Southern Saharan part of Libya known as the Fezzan, was given by Herodotus, and later adopted by Roman and Arab sources.

According to Herodotus in his famous work “The Histories”, the Garamantes were a powerful kingdom, and they were the first to introduce the Greeks to the 4 horse chariots. He also claimed “The Garamantes lived further inland behind the Nasamones in the land of wild beasts….Again at the same distance to the west is a salt-hill and spring, just as before, with date palms of the fruit-bearing kind, as in the other oases; and here live the Garamantes, a very numerous tribe of people, who spread soil over the salt to sow their seed in. From these people is the shortest route—thirty days' journey—to the Lotophagi; and it is amongst them that the cattle are found which walk backwards as they graze. The Garamantes hunt the Ethiopian cave dwellers, or troglodytes, in four-horse chariots, for these troglodytes are exceedingly swift of foot—more so than any people of whom we have any information.”

According to Pliny the Elder and Tacitus

The Garamantes would consistently raid the Roman coastal settlements, and did not easily give in to the Romans. “Up to the present, it has been found impracticable to keep open the road that leads to the country of the Garamantes, as the robber bands of that people have filled up the wells with sand, which wells do not require to be digged to any great depth, if you but have knowledge of the locality.”

Archaeological Finds

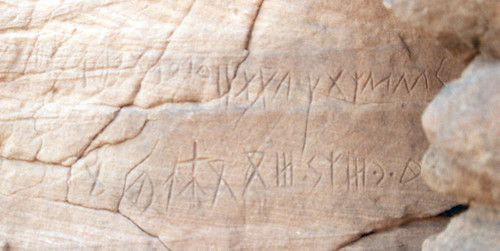

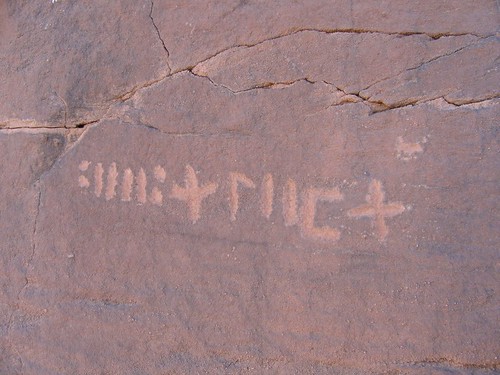

Archaeologist have discovered numerous rock art in the area where the Garamante kingdom was located. Also uncovered was a temple, trading market, and home to approx. 10 thousand residents, and a sophisticated irrigation system which proved they were an advanced farming society as well as a merchant society that traded salt and slaves. The ruins include numerous tombs, forts, and cemeteries.

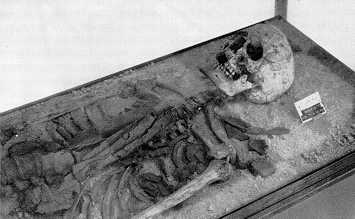

“This is the second volume resulting from a multidisciplinary investigation in the territory of the Garamantes, the powerful kingdom of southern Libya whose existence is roughly contemporary with that of ancient Greece and Rome. Surveys and excavations of Garamantian sites were initially conducted by a number of scholars including Charles Daniels, who worked in the 1960s and 1970s. The Fazzan Project, led by David Mattingly from 1997 to 2001, was designed to augment the research of Daniels, and after his premature death was also charged with bringing his research to publication. The major goal of the Fazzan Project was to understand the role of the Garamantes within the history and exploitation of the Sahara over the long term. Volume 2 publishes all the sites recorded by both Daniels and the Fazzan Project in the main settlement area (Wadi al-Ajal) and outlying districts occupied by the Garamantes. It also presents radiocarbon dating evidence, the pottery typology, lithics, metalworking and other industrial activities, and coins, beads, leather, paper, glass, and other small finds.

The Fazzan region is situated at a major crossroads in the central Sahara approximately 1000 km from the Mediterranean coast. The earliest occupation documented in Volume 2 consists of small bands of hunter-gatherers exploiting quartzite deposits to make Acheulean handaxes from c. 400,000 BP. There is substantial evidence for the Middle Paleolithic until c. 70,000 BP when an arid phase set in, resulting in the drying up of a large lake in the 3-10 km-wide by 150 km-long Wadi al-Ajal. At that time the Fazzan was abandoned and re-occupation did not take place until c. 10,000 BP, when mobile hunter-gatherers returned. Growing aridity led to the initiation of pastoralism and agriculture perhaps as early as 8,000 BP. During the last 5,000 years, rainfall has been negligible, and therefore agricultural production increasingly depended on the ability to acquire water from underground sources. This was most notably achieved by the use of foggaras, subterranean tunnels which tap aquifers and lead water to cultivated plots. A minimum of 617 of these foggaras are known in the Fazzan. They provided for the basis for substantial human occupation, with population numbers possibly in the tens of thousands at their peak in the first three centuries CE (Daniels estimated 120,000 Garamantian tombs could be found along the Wadi al-Ajal). The majority of the population lived in towns and villages, though they were stereotyped as transhumant pastoralists by Greek and Roman authors. Garamantian civilization declined from c. 400 CE. The Fazzan existed outside Islamic control until the 11th or 12th century, but new trans-Saharan trade routes developed through Morocco and Algeria, and the influence of the Garamantes on the development of the desert diminished.”

bmcr.brynmawr.edu/2010/2010-02-79.html

Garamante Chariot

Ptolemic Map of African showing Garamantes settlements (reproduced in the 15th century)

The name first assigned to this group of Africans that once thrived in the Southern Saharan part of Libya known as the Fezzan, was given by Herodotus, and later adopted by Roman and Arab sources.

According to Herodotus in his famous work “The Histories”, the Garamantes were a powerful kingdom, and they were the first to introduce the Greeks to the 4 horse chariots. He also claimed “The Garamantes lived further inland behind the Nasamones in the land of wild beasts….Again at the same distance to the west is a salt-hill and spring, just as before, with date palms of the fruit-bearing kind, as in the other oases; and here live the Garamantes, a very numerous tribe of people, who spread soil over the salt to sow their seed in. From these people is the shortest route—thirty days' journey—to the Lotophagi; and it is amongst them that the cattle are found which walk backwards as they graze. The Garamantes hunt the Ethiopian cave dwellers, or troglodytes, in four-horse chariots, for these troglodytes are exceedingly swift of foot—more so than any people of whom we have any information.”

According to Pliny the Elder and Tacitus

The Garamantes would consistently raid the Roman coastal settlements, and did not easily give in to the Romans. “Up to the present, it has been found impracticable to keep open the road that leads to the country of the Garamantes, as the robber bands of that people have filled up the wells with sand, which wells do not require to be digged to any great depth, if you but have knowledge of the locality.”

Archaeological Finds

Archaeologist have discovered numerous rock art in the area where the Garamante kingdom was located. Also uncovered was a temple, trading market, and home to approx. 10 thousand residents, and a sophisticated irrigation system which proved they were an advanced farming society as well as a merchant society that traded salt and slaves. The ruins include numerous tombs, forts, and cemeteries.

“This is the second volume resulting from a multidisciplinary investigation in the territory of the Garamantes, the powerful kingdom of southern Libya whose existence is roughly contemporary with that of ancient Greece and Rome. Surveys and excavations of Garamantian sites were initially conducted by a number of scholars including Charles Daniels, who worked in the 1960s and 1970s. The Fazzan Project, led by David Mattingly from 1997 to 2001, was designed to augment the research of Daniels, and after his premature death was also charged with bringing his research to publication. The major goal of the Fazzan Project was to understand the role of the Garamantes within the history and exploitation of the Sahara over the long term. Volume 2 publishes all the sites recorded by both Daniels and the Fazzan Project in the main settlement area (Wadi al-Ajal) and outlying districts occupied by the Garamantes. It also presents radiocarbon dating evidence, the pottery typology, lithics, metalworking and other industrial activities, and coins, beads, leather, paper, glass, and other small finds.

The Fazzan region is situated at a major crossroads in the central Sahara approximately 1000 km from the Mediterranean coast. The earliest occupation documented in Volume 2 consists of small bands of hunter-gatherers exploiting quartzite deposits to make Acheulean handaxes from c. 400,000 BP. There is substantial evidence for the Middle Paleolithic until c. 70,000 BP when an arid phase set in, resulting in the drying up of a large lake in the 3-10 km-wide by 150 km-long Wadi al-Ajal. At that time the Fazzan was abandoned and re-occupation did not take place until c. 10,000 BP, when mobile hunter-gatherers returned. Growing aridity led to the initiation of pastoralism and agriculture perhaps as early as 8,000 BP. During the last 5,000 years, rainfall has been negligible, and therefore agricultural production increasingly depended on the ability to acquire water from underground sources. This was most notably achieved by the use of foggaras, subterranean tunnels which tap aquifers and lead water to cultivated plots. A minimum of 617 of these foggaras are known in the Fazzan. They provided for the basis for substantial human occupation, with population numbers possibly in the tens of thousands at their peak in the first three centuries CE (Daniels estimated 120,000 Garamantian tombs could be found along the Wadi al-Ajal). The majority of the population lived in towns and villages, though they were stereotyped as transhumant pastoralists by Greek and Roman authors. Garamantian civilization declined from c. 400 CE. The Fazzan existed outside Islamic control until the 11th or 12th century, but new trans-Saharan trade routes developed through Morocco and Algeria, and the influence of the Garamantes on the development of the desert diminished.”

bmcr.brynmawr.edu/2010/2010-02-79.html

Garamante Chariot

Ptolemic Map of African showing Garamantes settlements (reproduced in the 15th century)